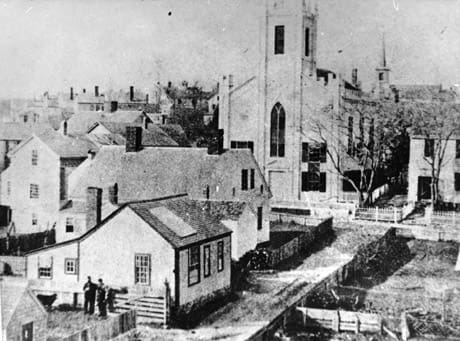

Amherst, MA 1879

Compartmentaization connects another Great Amherst Fire in Canada, like we saw with St. John and Saint John

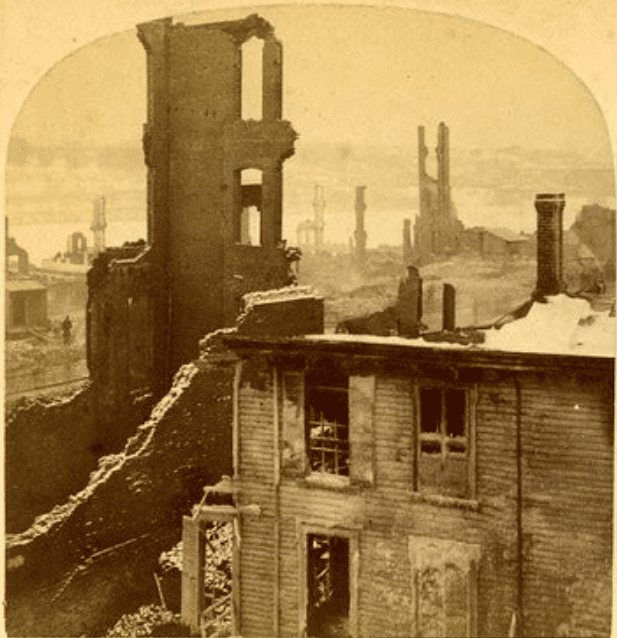

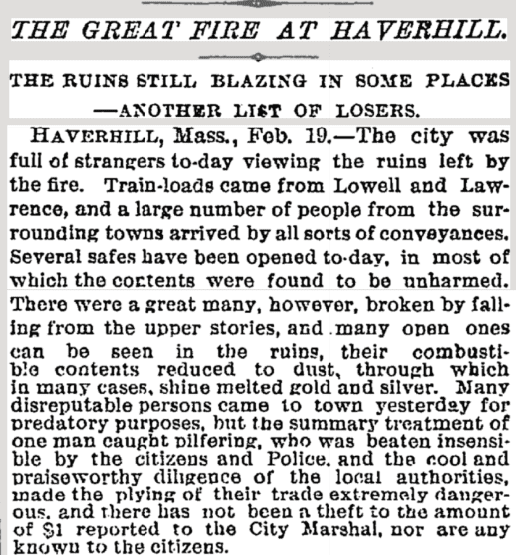

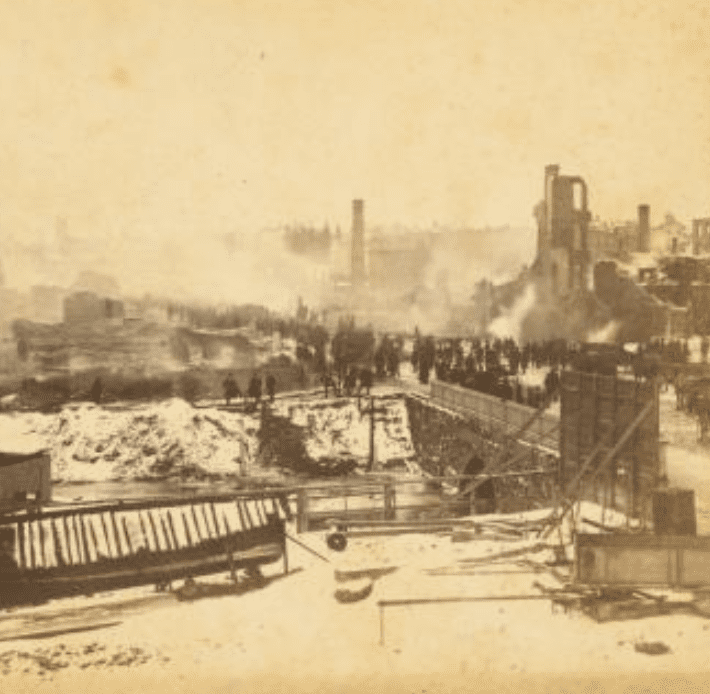

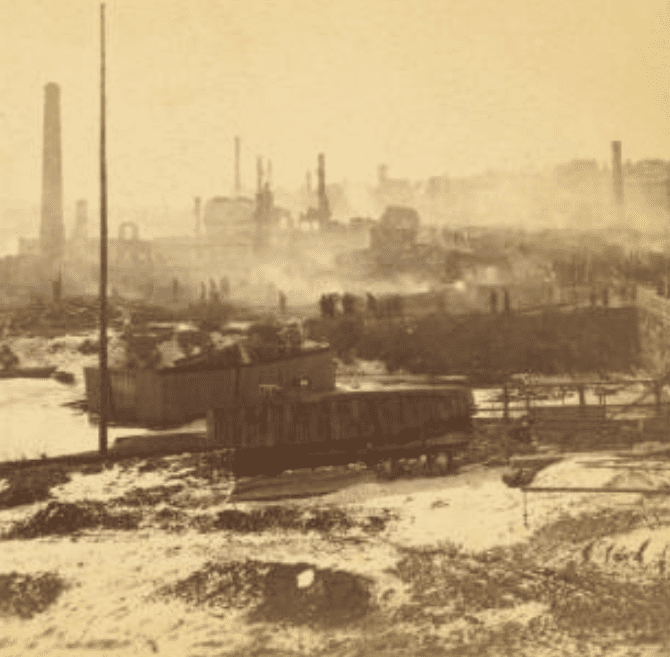

Haverhill’s Great Conflagration of 1882

Several facts and details never published about Haverhill’s Great Conflagration of 1882 were recounted in an interview with former Fire Chief O.M. West on February 17, 1913, the 31st anniversary of the disastrous fire. The following reflects some of his interesting recollections.

CONDITIONS AT THE TIME OF THE FIRE

The chief had brought to the attention of building owners and shoe manufacturers alike a hazardous condition where wooden doors swung back against heated stoves. He ordered that the wooden doors be covered with tin. Instead of correcting the hazardous condition, the owners instead elected to increase the insurance on their property. A few days before the fire, Chief West appeared before the City Council to request additional fire apparatus and that the job of steam engine driver be made full time so the driver could remain at the firehouse. Since the total fire loss the year before had been only sixteen hundred dollars, council members were not receptive to his request. In those days there was no fire alarm system that would indicate a fire or its location. Instead, the old village method of alarm was often used. Citizens yelling “fire” and the ringing of church bells or a local whistle was common. The home of Chief West was at 126 Water Street, opposite the Water Street fire station that housed the “Essex” steam engine.

According to Chief West, the fire department was not well organized then. It had no modern fire apparatus with which to fight a fire of any magnitude. There were no permanent firemen. Citizens and call firemen alike heeded the call of fire. The only permanent men employed were the drivers of the three steam engines then in use. The drivers were often involved in other lines of work for the city. At the time of the fire, one of Haverhill’s steam fire engines was at the Amoskeag Fire Engine Works in Manchester, New Hampshire being overhauled. An old steamer of little worth became a temporary replacement.

Days before the fire, Chief West inspected the factories that were later destroyed by the fire, including the one in which the fire is believed to have started.

The fire was discovered at 11:45 Friday night, February 17, 1882, one of the coldest nights of the winter. The thermometer registered six degrees below zero and there was a gale blowing. Chief West was awakened from a sound sleep by his mother-in-law, Mrs. Harriet Treab. (See Note:). As Chief West hurried from his home he heard no alarm indicating a fire; he did however smell smoke from the steamer.

At Elm Corner he met a man who informed him that there had been a fire earlier, in a pharmacy, on Mt. Washington, but it had been extinguished. It wasn’t until he proceeded to Eaton’s Corner and looked along Washington Street that Chief West saw the blaze. Realizing that it was in a wooden block and that some buildings contained inflammable material, he immediately upon arrival at the scene gave an order for additional help and had telegrams sent to fire department officials in nearby communities. Chief West highly commended the Lawrence firefighters for the heroic work they did in the intense cold, stating that they undoubtedly prevented the fire from spreading to the east side of Essex Street. At that time the water system had a pressure of only fifteen or twenty pounds and much of the hose in use that night froze up. Due to these conditions, one firefighter put water on the burning coping of one building by playing a hose onto the blaze while his fellow firefighters held him by the legs from the roof of the building involved.

At 5:00 am Saturday morning Chief West saw the chimney of the Tilton building on Wingate street begin to topple and shouted a warning to firefighters and spectators. His warning was too late, however, for firefighters Joseph St. Germain and George Whittier. The next day Joseph St. Germain was buried with great honors. Thousands of citizens joined in a demonstration of grief over his tragic and untimely death. Whittier, though seriously injured, recovered.

New Hampshire Xmas Fires

What are the chances — three fires just a few years apart, all at Christmas?

The first was in 1802, on December 26; the second, in 1806 on December 24 and the third, in 1813 on December 22. No sooner had the city begun to rebuild, twice, when flames once again leveled it.

The 1802 fire started the day after Christmas in an old wooden house near Market Square. It roared through the city, destroying more than 100 buildings. Most property owners had no insurance; private charity provided the only relief. As a result, the NH Fire and Marine Insurance Company was incorporated.

Four years later, on Christmas Eve, a row of wooden commercial buildings along the river began to burn, having started in a poorly insulated hearth. Flames destroyed all of the buildings along the river, plus the historic St. John’s Church, built of wood in 1732.

Property damage totaled $130,000, $6.5 million in today’s dollars.

The 1813 fire — called “the Great Portsmouth Fire” — was the worst of them. It broke out near Court and Pleasant Streets and engulfed everything from there to the river. The blaze could be seen as far away as as Salem, Mass. Fifteen city acres and 108 buildings were destroyed. The insurance company, established after the first fire, went bankrupt.

A year later the Legislature passed the Brick Act, which required that all new city buildings more than 12 feet high be built of brick. As a result, today the central part of the city, north of Court Street, is mostly brick.

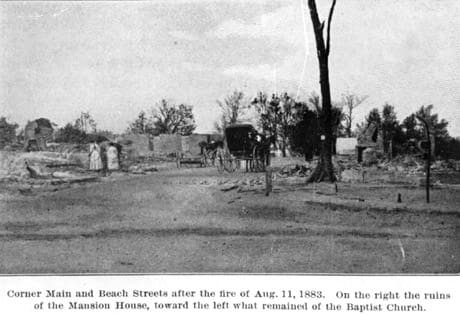

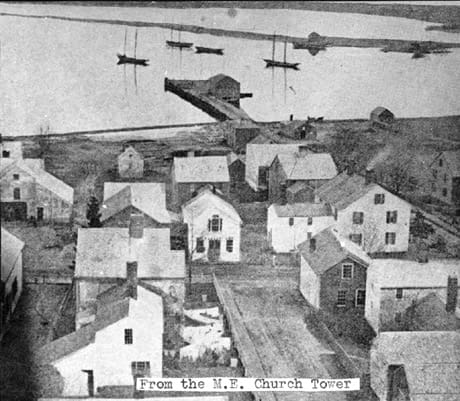

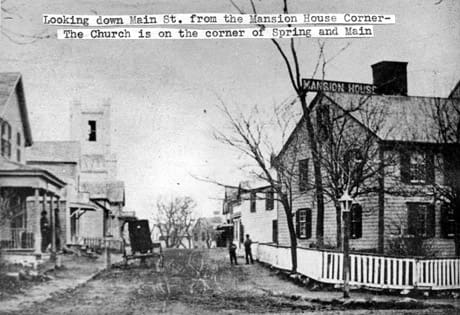

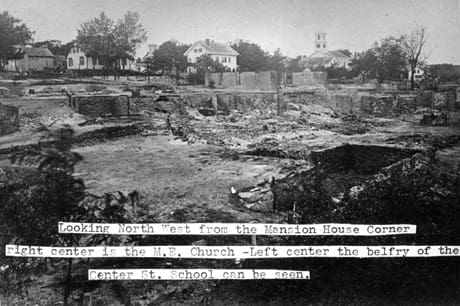

Marthas Vineyard, 1883

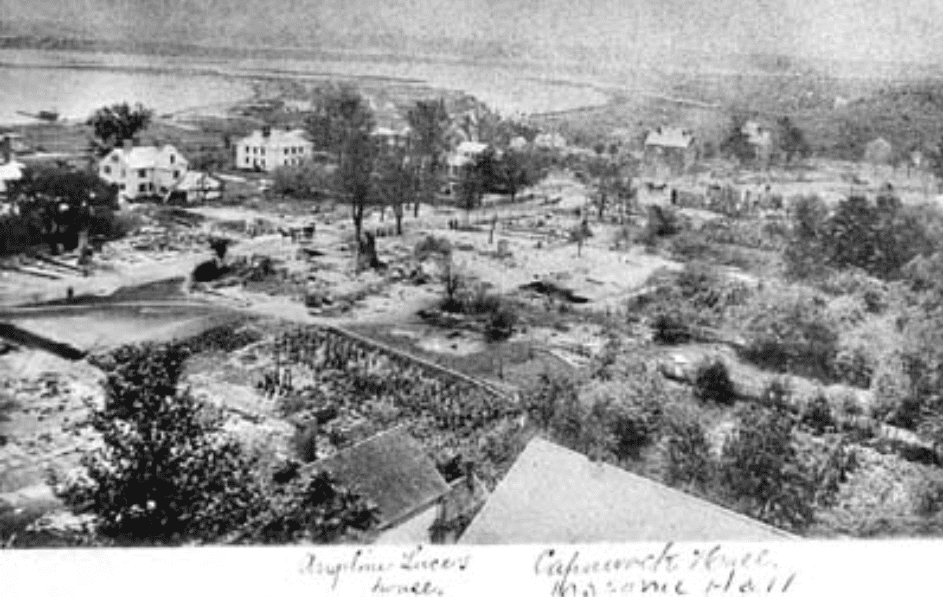

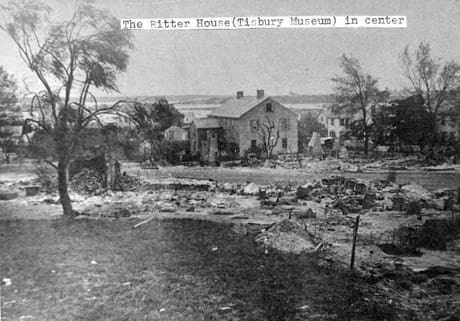

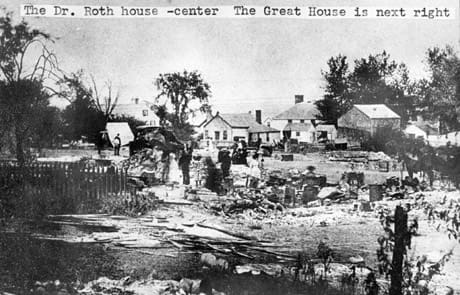

The Tisbury fire, which began one summer evening in the very heart of downtown Vineyard Haven, destroyed 62 buildings valued at $200,000. Photographs of the center of the village the next morning show smears and patches of black spread across a grid of lanes and roads. Every store but one burned to the ground.

Samuel Keniston was an energetic editor, but one weeps over his judgment here. Whatever he wrote about the fire, which happened on a weekend, he put into the Monday edition of the Cottage City Chronicle, a supplement printed for vacationers in Oak Bluffs Ñ and that copy of the Chronicle is lost.

In the paper of record at the end of the week – the Gazette – he merely picked up the story where the Chronicle left off, writing about the buying and selling of ruined lots and of early efforts to rebuild, then offering little more than a few editorial notes about how well the town had tried to fight the conflagration.

Almost 40 years later, fortunately, a pair of youthful new editors – Elizabeth Bowie and Henry Beetle Hough – decided to record the story again, interviewing Vineyard Haven residents who still remembered it. For the sake of history, we excerpt this excellent account of the Tisbury fire.

On a black night almost 37 years ago, August 11, 1883, a summer visitor stood on Vineyard Haven wharf. As the northeast wind whistled past he shuddered and said, “what a night for a fire.” A chance remark which anyone might make as he thought of a town built of wood, with no means of fighting a blaze except the humble cistern and the bucket brigade. But uttered that night it was remembered through the years. For the fire came.

Cape May, 1878

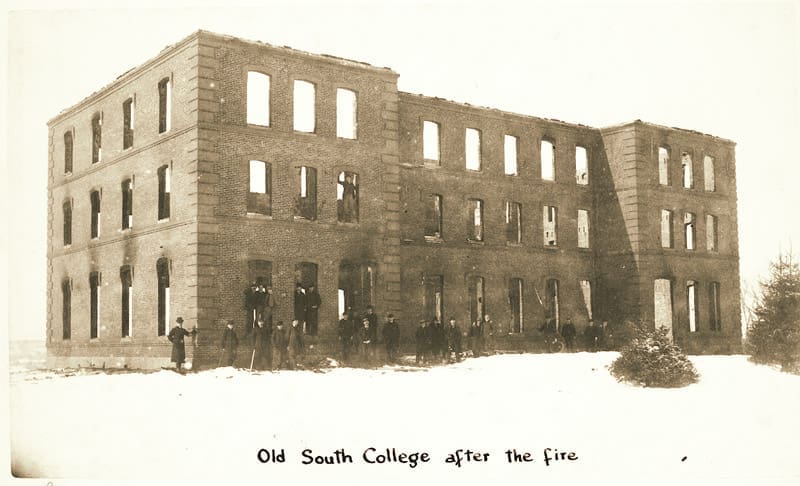

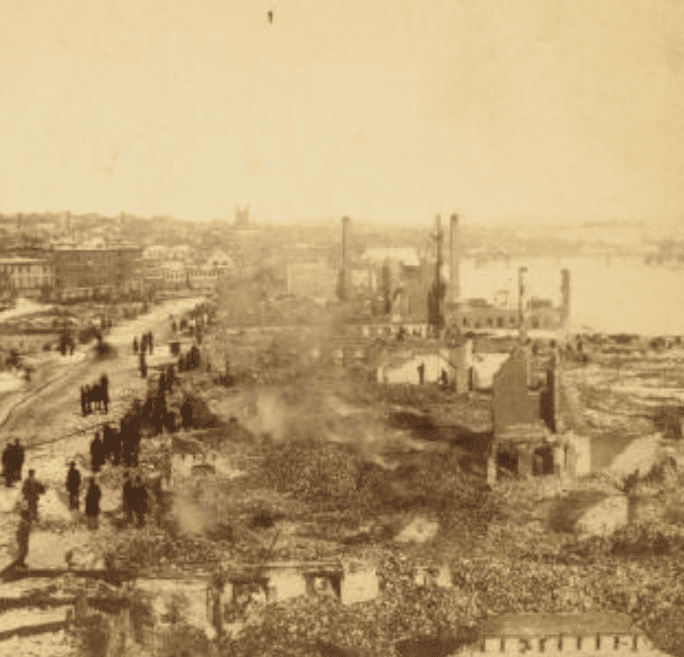

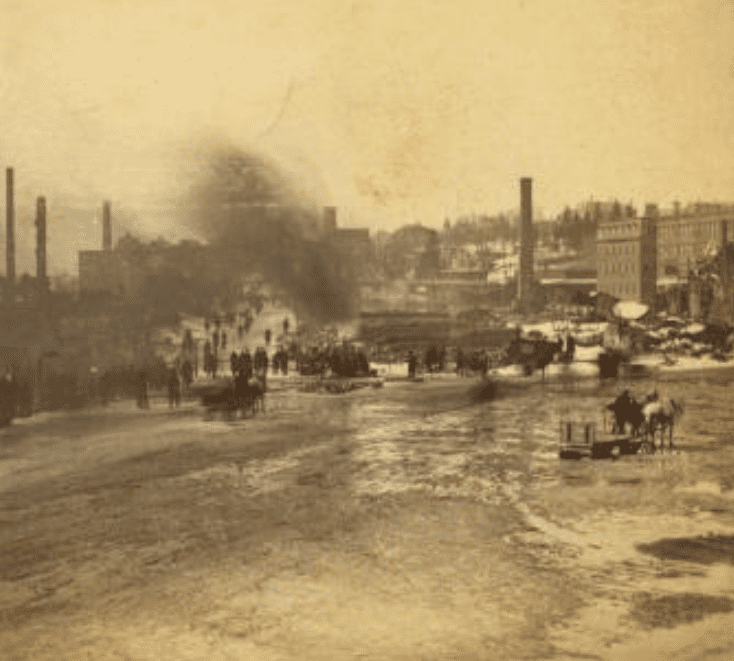

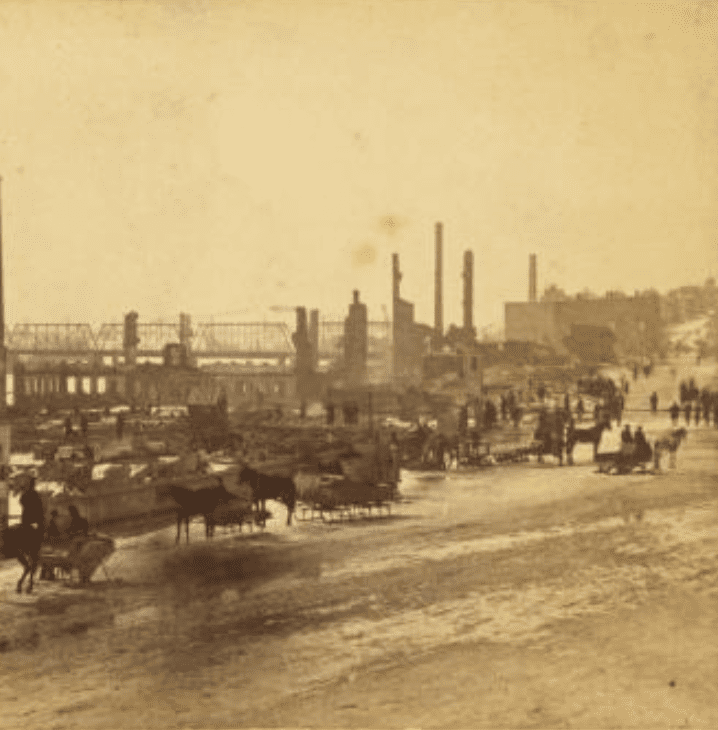

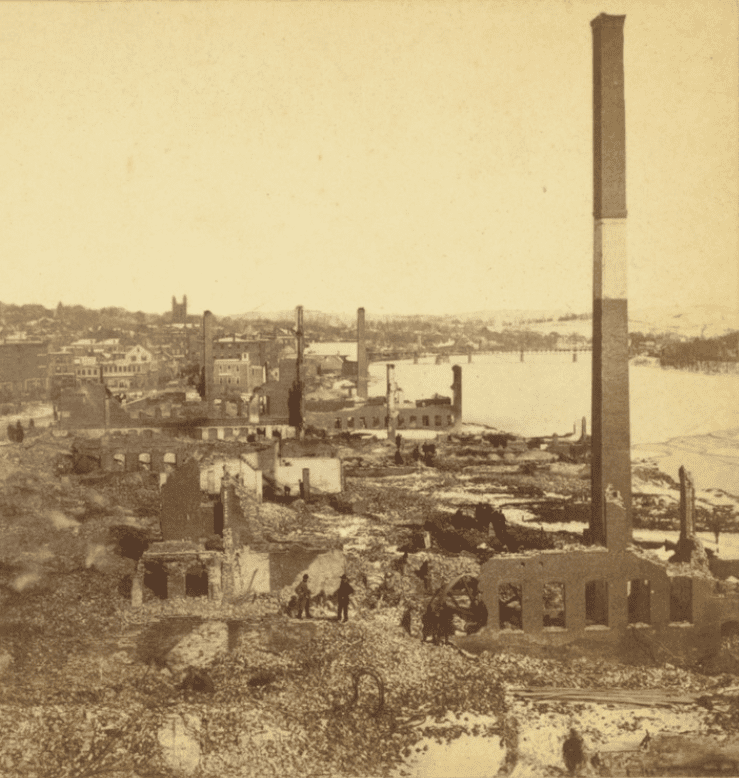

No details yet but this image turned up and matches the rest